The History of Tattoos: From Ancient Tribes to Modern Art

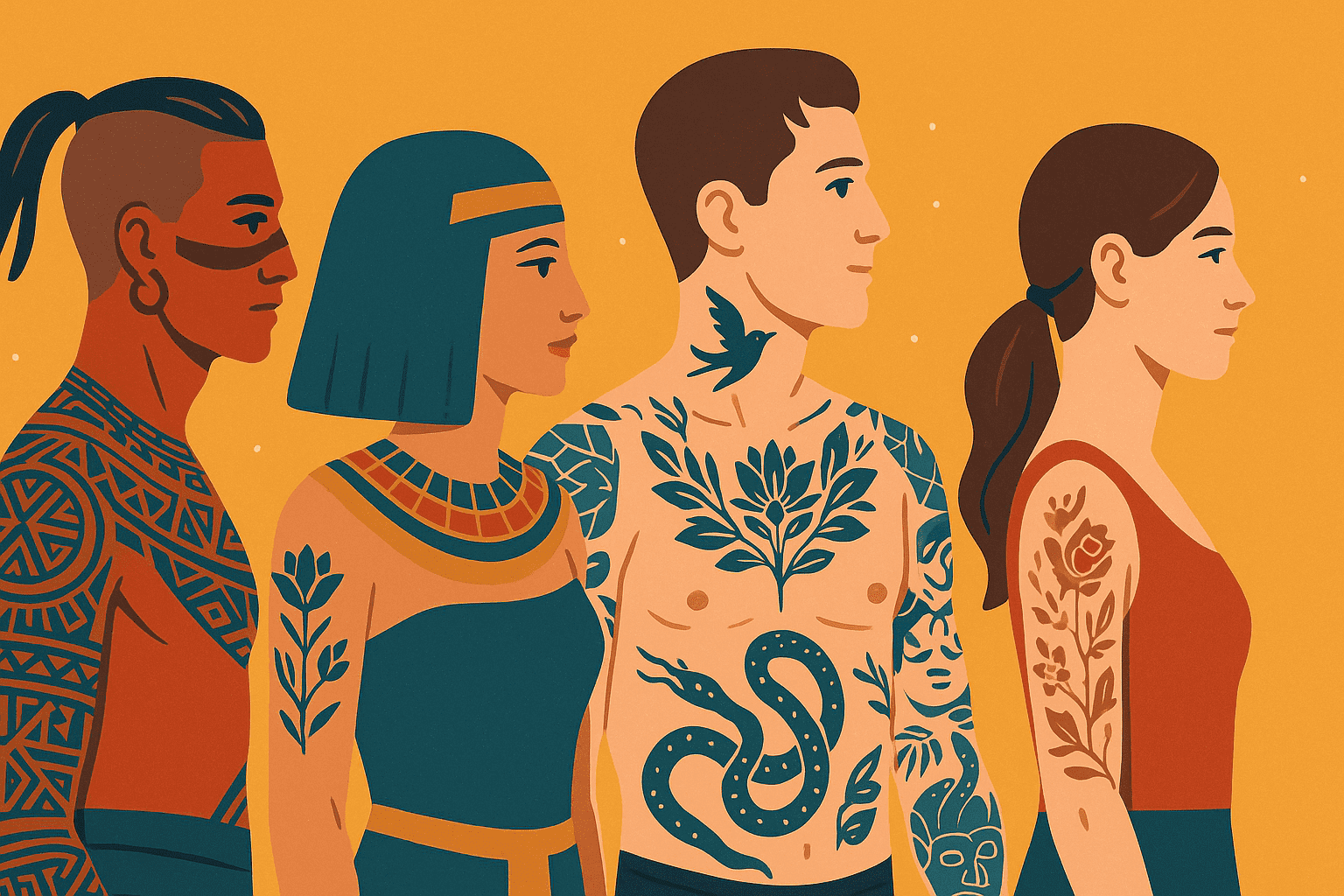

Tattoos are more than skin-deep—they are living symbols of identity, tradition, rebellion, and art. Stretching back thousands of years, the practice of tattooing has traversed continents, cultures, and centuries, shifting from sacred rituals to mainstream fashion statements. To understand the rich and varied story of tattooing is to look into humanity’s evolving relationship with the body, symbolism, and self-expression.

Ancient Beginnings: Tattoos as Tribal Identity

The earliest evidence of tattooing dates back to over 5,000 years ago. The famous discovery of Ötzi the Iceman, a naturally mummified man from around 3300 BCE found in the Alps, revealed more than 60 tattoos etched into his skin. Interestingly, these tattoos aligned with areas of joint and spinal degeneration, suggesting they may have had therapeutic or ritualistic significance—perhaps an early form of acupuncture or spiritual healing.

In ancient Egypt, tattoos were practiced as early as 2000 BCE. Mummies of Egyptian women show intricate dot and dash patterns across their bodies, possibly tied to fertility, protection during childbirth, or religious beliefs.

Meanwhile, in Polynesian and Maori cultures, tattoos—known as tatau and moko respectively—carried deep significance. They were rites of passage, indicators of status, and historical records inscribed directly onto the skin. These designs were often painfully etched with bone tools, making the process as much a test of endurance as a declaration of belonging.

Tattoos in Ancient Civilizations: From Ritual to Rebellion

In Japan, tattooing emerged around 10,000 BCE during the Jōmon period, though the tradition as we know it began to flourish centuries later. While early tattoos may have been spiritual or decorative, by the Edo period (1603–1868), elaborate full-body tattoos (irezumi) became associated with both firefighters (as protective charms) and outlaws, such as gamblers and members of the yakuza. These tattoos, often featuring dragons, koi fish, and mythological scenes, were hidden beneath clothing, forming an underground art form.

In Greco-Roman culture, tattoos were typically punitive. Slaves, criminals, and prisoners of war were marked, making tattooing a symbol of stigma and control rather than honor. Similarly, early Christian Rome viewed tattoos as desecration of God’s image, leading to a temporary decline in the practice across Europe.

Tattoos in Indigenous Cultures: Sacred and Symbolic

Across the globe, indigenous groups have used tattoos to connect with ancestors, deities, and the natural world. In Alaska and Northern Canada, the Inuit and Yupik peoples practiced facial tattooing among women—lines on the chin or across the face that marked puberty, marriage, or bravery. These tattoos were often spiritual, believed to guide souls to the afterlife.

In the Philippines, tattooing was both a mark of valor and a rite of passage. The Kalinga warriors, for instance, earned tattoos by proving themselves in battle. Known as the “art of the brave,” each tattoo was a badge of honor. This heritage survives today in artists like Whang-od Oggay, a centenarian tribal tattooist who still hand-taps traditional ink into skin using citrus thorns and soot.

The Western Revival: From Sideshow to Studio

Tattoos began to reemerge in Europe during the 18th century, thanks to sailors encountering the practice in the Pacific. Captain James Cook’s voyages brought the term “tattoo” into the English language and sparked a maritime tradition of tattooing among sailors, who wore anchors, swallows, and compasses as symbols of luck, love, and survival.

By the late 19th century, tattooing had become a sideshow attraction. Figures like Captain George Costentenus, a fully tattooed man who claimed to be kidnapped and inked by natives, toured circuses in Europe and America. While many of these stories were exaggerated or fabricated, they captivated public imagination.

In 1891, Samuel O’Reilly patented the first electric tattoo machine in New York, adapted from Thomas Edison’s autographic pen. This revolutionized the industry, making tattoos faster, less painful, and more accessible.

Modern Era: Art, Identity, and Acceptance

In the 20th century, tattoos remained subcultural—embraced by bikers, prisoners, punks, and rebels—but still carried a social stigma. It wasn’t until the late 20th and early 21st centuries that tattoos began to shift from taboo to trend.

Today, tattoos are celebrated as personal art forms, expressions of individuality, grief, love, identity, and transformation. Television shows like Ink Master and LA Ink turned tattoo artists into celebrities. Tattoo conventions draw global crowds, and studios now boast high hygiene standards and diverse portfolios.